By JOHN OWEN HAVARD

Review of Jonathan Swift: The Reluctant Rebel, by John Stubbs

New York: Viking, 2017

The third voyage of Gulliver’s Travels features a political experiment. After sending Gulliver to Lilliput, where he finds himself lauded as a giant, then onto Brobdingnag, where his kind are scorned as vermin, Jonathan Swift confronts his hero with a fantastical world of futuristic projects—including a proposed cure for political division. In the experiment, two political opponents exchange half their brains with each other. Their political opinions, the inventors speculate, will thereby balance out, tempering their convictions and defusing their zeal. There was just one problem: the procedure has a low success rate, proving fatal in all cases.

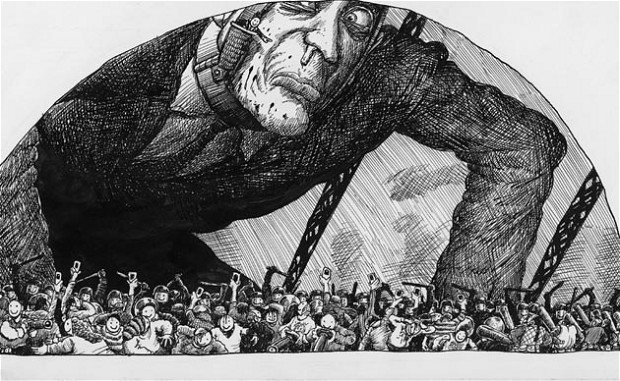

Swift was the most brilliant satirist of his age—perhaps, indeed, of any age. 350 years after his birth he remains a weatherworn beacon for our lost-feeling times. We may one day graduate to an enlightened future in which his damning conclusions about human tribalism and short-sightedness, bureaucratic cruelty and all-pervasive barbarism will no longer apply. For the time being, we remain captured within his unforgiving vision. Even our own projected escapes remain destined, his satire brilliantly reminds us, to become as risible as the world they seek to transform. Recent defenses of Enlightenment and the ability to overcome shortsightedness are the latest to fire the Lilliputian arrows of reason against the behemoths overshadowing our own age.

Still, there are good reasons that political stalwarts including W.B. Yeats, George Orwell, and Edward Said were drawn to Swift’s example. The author of A Modest Proposal has been hailed as a critic of corruption and defender of liberty, not least in his Irish homeland. Yet Swift’s writings present uncomfortable challenges. There are the frequent ugliness and extremity: his misogyny and contempt for the poor, his preoccupation with women’s sweaty armpits and with everybody’s fecal matter. And then there are his own politics. He may have become an Irish patriot hero, but he still hated Irish people. In England, Swift was a canny political operator, if also an anxious outsider, who dreamed of dismantling the Administrative State in the name of an unspoiled political past. Swift was a strange breed of political animal. Which sides won out remained a debate for his own age—one now reanimated for our own.

In his sharp, lyrical biography Jonathan Swift: The Reluctant Rebel, John Stubbs has returned these warring impulses squarely to the foreground. Fluctuating between orthodoxy and rebellion, Swift was at one and the same moment “a stern authoritarian and a daring cultural bandit.” Stubbs’s rich and learned study gives us Swift as an often brutal advocate for established religion and ruthless opponent of progressive politics. At the same time, Swift appears torn between his ties to the establishment and his qualified advocacy for the Irish (even as “he made no attempt to deny” that Ireland might be “beyond salvation” and “might even deserve the desolation it faced”). Swift hardly provides a salutary vision for the future. But his rebelliousness, however conflicted and reluctant, tempered by his cracked humanity and dark humor, may still provide a tonic for our own divided present.

During the first age of parties, political division and partisan animus were felt throughout the social fabric. Amidst the heightened polarization of the early eighteenth century, Swift lamented, the “dogs in the street” appeared “more contumelious and quarrelsome than usual” (a “committee of Whig and Tory cats” aligned with the respective sides of parliament, he noted elsewhere, kept him awake with their hideous screeching on his rooftop). He described the pervasive distrust as a systemic problem:

How has this Spirit of Faction mingled it self with the Mass of the People, changed their Nature and Manners, and the very Genius of the Nation? Broke all Laws of Charity, Neighbourhood, Alliance and Hospitality; destroyed all Ties of Friendship, and divided Families against themselves? And no wonder it should be so, when in order to find out the Character of a Person; instead of enquiring whether he be a Man of Virtue, Honour, Piety, Wit or good Sense, or Learning; the modern Question is only, Whether he be a Whig or a Tory, under which terms all good and ill Qualities are included.

This kind of conflict had defined politics in England and Ireland “for as long as anyone could remember” Stubbs reminds us. But the partisanship deforming the country had been cranked into a new gear, creating the “Rage of Parties” that burned through the post-1688 decades. The result was an all-too-familiar pattern of escalation. As historian Mark Knights has noted in his invaluable study of political misrepresentation, partisan disagreement extended to competing accounts of what was true and false. Division and distrust were quickly inflamed into accusations of outright dishonesty. Rhetorical excesses led to expressions of resentment and anger from the opposing side—which in turn bred further division. In response to accusations that they had lied and were deranged, each party responded with inflated accusations of their own. Yet these exaggerations themselves bordered on lies. And their vehemence risked making those issuing them seem deranged.

Can’t we all get along? Well, no, Swift reminds us—we can’t. Not when fundamental questions are at stake. Not while, fantastical brain transplants notwithstanding, we remain in our own heads, compelled by impulses we may never fully control nor comprehend. For all his satires of arcane religious differences (wars erupt in Gulliver’s Travels over the right side on which to break open an egg), the specter of sectarian conflict drove Swift’s lifelong commitments to promoting organized religion. (As Dean of St. Patrick’s Cathedral, Swift showed little doubt that there was a right way to crack an egg.) Those religious commitments had staunch political counterparts. “There was an England he adored,” Stubbs notes, “and one he loathed.” The nation Swift idealized was grounded in an unspoiled, ancient past. The country he hated had too many levels to count, but the “topmost layer of dishonor” had been laid in his lifetime and consisted of the “muck that covered the land” when beloved, pious Anne was succeeded by a wave of German-speaking Georges. The Queen’s reign had been Swift’s golden age, in which he achieved prominence as “one of the leading propagandists” and the foremost political writer of the time, “brought on board for the mayhem he was capable of creating” as a “mud-slinger” of immense subtlety and power.

He had arrived on the scene as an outsider, cursing his Irish birth. But he rose to become “the epitome of an insider, a voice of the establishment” writing jolly letters to his young female correspondents celebrating his time at the center of power. “Few of this generation can remember any thing but war and taxes, and they think it is as it should be; whereas ‘tis certain we are the most undone people in Europe,” he lamented. Make England Great Again. But within a few short years, the political tides reversed. Swift’s party was swept out of power and the political ranks were filled with his political enemies, with “shattering” reprisals for all those associated with his side. Swift’s enemies were in power and he was exiled to Ireland, trapped in the despised homeland for the remainder of his life. “I can assure you the scene and the times have depressed me wonderfully,” he wrote to Alexander Pope from Dublin. But his loss was our gain. From his time as the Dean of St. Patrick’s would come his most excoriating attacks on the English elite, his unlikely ascent as an Irish political hero, and Gulliver’s Travels—the greatest satire of his, perhaps of any, age.

In his account of a lifetime working with schizophrenics, Christopher Bollas recalls a patient at a Bay Area facility in the 1960s who was convinced that planes shrink their passengers in order to take off. The young man was terrified that he and his family would be miniaturized. During a subsequent trip to a swimming pool, Bollas does not understand at first why the children screamed upon entering the water, thinking that “perhaps they felt that it would dissolve them.” He then realizes that the body appears distorted below the water line and that “the children would see this and panic, assuming that the water was bending their bodies.” In his therapeutic practice, Bollas expolains, he strives to assist his patients in stitching their warped perceptions back together with a shared reality. In the process, he has expanded his appreciation for the distortions to which we all remain liable. The era of the Vietnam War nonetheless presented an especially acute challenge. “Psychotherapists, especially those working with psychotic children, found themselves in an increasingly tenuous position,” Bollas recalls, during a period when “the war zone itself represented a massive denial of reality.” Despite often suffering from psychosis, returning soldiers had the best insight into the reality on the ground. Yet they could not communicate these truths with the wider culture. There was little hope, moreover, for grounding the psychologically disturbed back in real life: this was a period in which the world itself had seemed to go mad.

Gulliver’s Travels depicts its hapless voyager confronting a series of distant kingdoms and alien peoples, with none-too-subtle digs at the political corruption Swift had seen taking hold over his lifetime. But these localized critiques of a debased political world give way to mind-bending shifts in perspective. In the second book, Gulliver finds himself—formerly a giant to the miniature people of Lilliput—become tiny relative to the gigantic inhabitants of Brobdingnag. Following his encounters with the futuristic land of ludicrous experiments, the fourth voyage introduces him to a race of hyper-rational horses. Gulliver shocks these grave, dispassionate creatures with his story of human violence; they in turn identify him with the sharp-clawed, tree-inhabiting “Yahoos,” a vicious species that their horse-overloads seek to exterminate. Gulliver’s Travels, Stubbs writes, “expressed in comic form Swift’s horror at ugliness, his despair at human depravity; but also his wonder and amusement at the way things change with perspective.” (“It is a fantasy written with inimitable literalness,” he adds, in a rare moment of opacity). Far from reconciling his conflicting political viewpoints, Gulliver finds himself driven around the bend. The book concludes with him unable to inhabit the human perspective; incapable even of cohabiting with his family, who now disgust him, he moves into a stable. Far from grounding him back in a shared reality, Gulliver concludes his book estranged from the entire human species. This is not my beautiful house, he says to himself. These are not my people. This world is insane. How did I get here?

Swift’s disorientation had multiple axes. From Ireland, the political crisis engulfing his political friends in England seemed unreal. As he watched on from Dublin—where he was increasingly hailed, at times uncomfortably Stubbs shows, for his interventions in local politics—Swift was newly struck by the pettiness of political ambition and a “sense of being a stranger to himself.” This disorientation was further accentuated by physiological conditions that afflicted him with bouts of acute dizziness. Even as the sensation caused by Gulliver’s Travels and Swift’s other late writings died down down, vertigo and deafness “remained his companions”; “the immobility and the gazing continued” and Swift, unlike Gulliver, “remained tied down, disturbed by sea-like sounds.” Swift’s early writings had at times veered close to the ravings of a madman. But writing for him became “not only a retreat but also a means of holding a still point amid his fits of dizziness, and staving off an existential vertigo that oppressed him even more.” Swift found a similarly unlikely focus in the gutter. Breaking into her dressing room, Strephon transforms his idealized female love object in Swift’s poem by opening the “Pandora’s Box” of her chamber pot. In response to the idea that order pervaded nature, Stubbs reminds us, Swift instead wrote “almost obsessively about dirt and shit, as a breathless insistence that the contrary was true.”

Jonathan Swift: The Reluctant Rebel excels in explaining how Swift’s warring impulses converged to create the driving passions of his work. There was “Swift the conformist” and “Swift the anarchic humorist”: “together they produced the satirical writer.” (A “third and silent element” informed by modern psychology—“one that grieved at lack of love and a sense of belonging nowhere, craving status, stability, and recognition to offset the gnawing effects of shame and insecurity”—also haunts these pages).

With the penetrating focus of Swift’s later work came a sharpening of his overall vision. Swift’s Irishness was unquestionably crucial in this regard, yet critics have struggled with how to explain its countervailing movements. Stubbs concludes deftly that Ireland was Swift’s “personal, emotional shorthand for all that was amiss with the circumstances of his life; a panoply of wrongs that included, incidentally, the sins of England.” As a “political exile in his country of birth,” Swift finally gave free rein to all sides of his vision: “dark and cruel poems” that depicted “the condition of ageing, partially blinded prostitutes”; “a voyeuristic verse tour of a lady’s dressing room, crowing over stains that were otherwise concealed”; and above all, the Yahoos, “the naked beshitten bipeds, biologically human, who lob their droppings at an understandably offended Gulliver.”

Swift has not wanted for biographers, from exhaustive treatments of his writings and political entanglements, to continued rummaging for evidence of his dealings with women. Beyond its compelling new framing of Swift’s warring impulses and impatience for pedantry, Stubbs breathes with a fresh sense of its subject, without seeking to break the mold of prior accounts. For one, the book abounds with wonderful detail. I am not sure whether I needed to know that native Irish people bleached their hair; I am glad I now do. This thick description, coupled with evocative character sketches, yields acute insight, as in this bravura passage contrasting Swift’s early experiences of fine-dining and bonhomie at the center of power with his poem describing a filthy deluge:

The description of the shower, and the mildewed, battered city it pounds, is an unsettling counterpoint to this chummy scene amid heavy silver cutlery and fine-cut glass, drolleries exchanged as the bottle circumnavigated the table; the poem contrasts sharply too with the high-handed rhetoric Swift was about to unleash on the government’s enemies. His head was turned, his vanity touched, but the “Description of a City Shower” suggests he was someone who could never be transported completely by rising in the world. Things he found repulsive held him, paradoxically, to earth, since he could not avoid them or remove them from his mind: a consciousness, never sentimental, of the poor and mortal in the streets outside; unease at the flock of a maid’s mop, and the marks it could not remove; the puddled earth; unspeakable riverbeds.

The great renaissance tragedians, in the words of T.S. Eliot, “saw the skull beneath the skin.” Swift saw the skid-marks in the linen: the streaks of humanity no idealism could bleach clean. At the end of his poem on the “Lady’s Dressing Room,” Strephon finds himself driven mad by the realization that “Celia, Celia, Celia shits.” Yet Swift’s excremental vision of mankind was also one of qualified salvation, grounded by his ties to the madhouse of Ireland and the muddy, puddled earth. “Gaudy tulips” spring from the dung and disorder of the dressing room. At the bottom of Pandora’s Box, as Swift knew, remained Hope.

Facing the end of his life, Swift donated the remainder of his estate, such as it was, to an insane asylum—in Dublin, of course. “Verses on the Death of Dr. Swift” concludes with the assessment of an indifferent spectator:

He gave the little wealth he had

To build a house for fools and mad;

And show’d by one satiric touch,

No nation wanted it so much.

That kingdom he hath left his debtor,

I wish it soon may have a better.

Swift wrote this supposedly humble epitaph for himself. The word “touch,” with its delicately qualified hope, clues us in to his authorship. Swift’s words continue to lacerate the present; the derangement he imagined rearranges—and further deranges—itself in our own. Yet Swift may also continue to touch us. In confronting the fullness of his vision, we see ugliness, madness, and endless, hopeless division. But we also make contact with the hope advanced in a poem by Andrew Motion about a civic-minded bystander watching the turds left behind by a dog and its irresponsible owner. “On the one hand,” that poem concludes, “it’s only shit.” But “on the other, shit’s shit / And what we desire in the world is less, not more, of it.”

Posted on 25 September 2019

JOHN HAVARD is Associate Professor of English at SUNY Binghamton. He is author of Disaffected Parties: Political Estrangement and the Making of English Literature, 1760-1830 (Oxford, 2019).