By WILLIAM BAUDE

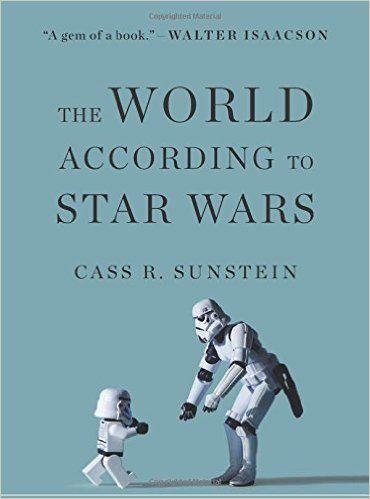

Review of The World According to Star Wars, by Cass R. Sunstein

New York: HarperCollins, 2016

I

Star Wars fans have adjusted to the possibility that worlds can be destroyed. The Galactic Empire has a particular penchant for global destruction, and three of the seven Star Wars movies center around a planet-destroying superweapon. Unfortunately, as true fans have recently discovered, that threat of destruction extends not only to the planet Alderaan and the other fictional planets in the movies, but to the richness of the Star Wars universe itself.

Despite its title, there is little destruction in Cass Sunstein’s new book, The World According to Star Wars. The book is an enthusiastic celebration of the Star Wars mythos and its lessons for life. Unfortunately, that celebration comes at the same time that the Star Wars universe itself is being destroyed. This means that while Sunstein’s book is delightfully fun, it still strikes the wrong note for true fans. There is much to love about The World According to Star Wars, but now is the time for a dirge.

II

Sunstein begins the book by dividing humanity “into three kinds of people: those who love Star Wars, those who like Star Wars, and those who neither love nor like Star Wars.” (xi) He explains that over the course of writing the book he moved from the second category to the first. Over the past few years, I have made the opposite journey. Eventually, I’ll explain why.

First, the book. It is partly about the development of the Star Wars movies and what makes them both great as a literary matter and so universally popular. But it is also about politics and behavioral economics (with points that will be familiar to those who have read Sunstein’s other books), and about families and life.

All of these seemingly unrelated topics are bound together by a unifying tone of madcap enthusiasm. Repeated interjections reveal, for instance:

-

Sunstein loves Taylor Swift: (“Perhaps you can imagine [a world] in which people don’t love Taylor Swift, but if so, I feel sorry for you; you’re not out of the woods.”) (36) (“Taylor Swift or Adele? (Swift, by a country mile, because her sense of mischief and fun ensures that she is never, ever, ever saccharine.)”) (84)

-

He recommends flirting with the Dark Side: (“Every human being needs to visit the Dark Side. Try it. Don’t linger.”) (xviii) (“Darth Vader … makes the dark side seem sexy. (It is, isn’t it?)”) (82)

-

And he is justly fascinated by a line from one of Lucas’s interviews, rejecting the argument that movies should kill off beloved characters: “I don’t like that and I don’t believe that.” (22) (Oops.)

Between these interjections are serious themes too. In a passage on regret and being good to one’s parents, Sunstein writes: “As you voice it, you might tear up a bit (as I’m doing now).” (99) A few pages later, he enigmatically notes: “Even if it’s temporary, an estrangement between a parent and child is extraordinaily painful. Been there, done that.” (102) Even so, the book maintains the pace and tone of a Star Wars movie. Sunstein notes that George Lucas “called the most characteristic feature of his films: ‘effervescent giddiness.’” (24) Sunstein has charmingly recreated that feature in his homage.

III

To the extent the book has a central argument, it is this: The Star Wars movies are great, but not because they were carefully designed or planned by George Lucas. Sunstein thus rejects what he calls “the myth of creative foresight. You end up having to make choices on the spot, and the directions you anticipate turn out not to be the direction in which you go. You can’t plan it out in advance.” (2-3) Instead, Star Wars’s universal appeal comes from the themes that eventually found their way into the movies – fathers and sons, redemption, and “its largest lesson”: an insistence “on freedom of choice.” (193)

There is much to this argument. As Sunstein explains, Lucas’s early ideas for the movies don’t sound very good. Even his later drafts omitted what became the most iconic parts of the original trilogy. And yet the original Star Wars movies are indeed great, and so they must be great for some reason other than “creative foresight.”

But the argument becomes less persuasive as we look beyond the first three Star Wars movies to consider the prequels, sequels, and many novels that shared the same universe. The successes and failures of those later movies and books show that excess improvisation and a lack of foresight can lead to artistic disaster. And they also reveal a different, important part of Star Wars’s appeal – the unique universe it created. Let me elaborate. . . .

IV

It all went wrong with The Force Awakens. (Sunstein says: “It doesn’t have anything like Lucas’ originality, but it’s still awfully good.” (154))

Science fiction and fantasy – Star Wars is both – make their mark by the worlds that they create. That world is part of what made the original Star Wars trilogy great. Watching it for the first time, you felt like you were joining the middle of the story – a story with a rich, fascinating past that you had to both take for granted and slowly discover. But more than that, you were joining a universe. The universe had lightsabers, force-wielding Jedi, elaborate starships and dozens and dozens of planets and alien species each of which (it was implied) had their own rich lives somewhere beyond the movies’ plot. Sunstein tells us that Star Wars “contains a whole world.” (xii) “A whole world” undersells it – Star Wars contained many, many worlds.

This is why The Force Awakens was a disappointment. What the franchise most needed was a plot that captured the vastness of the Star Wars universe – a plot that included things we had never seen before, and nobody named “Skywalker.” Instead, we saw Darth Vader’s family drama continued for yet another generation, and scenes and locations that were lifted right out of the original trilogy. (Even Rey, one of the most heralded new characters in the movie, is likely related to either Obi-Wan Kenobi or Luke Skywalker.) No moment in the The Force Awakens even approached the thrill of first seeing a lightsaber ignite.

What is more, the new movie physically compressed the Star Wars universe. In the original trilogy, we’re repeatedly reminded of the scale of the galaxy. Some planets are the “bright center to the universe” and others are “the planet that it’s farthest from.” It takes notable screen time for the characters to get from place to place. This contributes to the feeling of a real galaxy, with worlds full of possibility. By contrast, in The Force Awakens travel time is ignored, and even the newest world-destroying superweapon no longer needs to travel anywhere to destroy its targets.

The flatness of the new Star Wars universe is confirmed by the emotional emptiness of the movie’s climax. The good guys, the Resistance, fail to destroy the superweapon before it wipes out multiple planets that house, near as we can tell, much of the Republic’s population. This is a cataclysmic disaster. But in the movie, it passes as an afterthought. By this point the audience has stopped taking seriously the humanity of those off-screen worlds.

V

And unfortunately, the destruction of the Star Wars universe goes beyond that. The many worlds and races and characters of the Star Wars universe aren’t only something we could each imagine in the odd moments of the movies. They were written down, in hundreds of novels and comic books and games that all Star Wars fans could share as official common ground.

These products were called the Expanded Universe, and collectively they were the result of creative genius. While the stories were written by a large number of different authors, Lucasfilm required them to be continuous with one another. Characters introduced by one author might be developed by another; each book had to be consistent with the timeline established by the prior books. The result was a coherent galaxy richer than any one author could have created.

Some of this Expanded Universe material was really good – far better than The Force Awakens. One of the best was the saga of Grand Admiral Thrawn, an alien art-lover and war genius who faced discrimination in the Imperial navy, but reemerged after the Emperor’s death to take advantage of the New Republic’s bureaucratic weaknesses. That would have been a good movie.

Some of the material was pretty bad. (The Crystal Star?) But its membership in the Expanded Universe made it better – or at least worth reading. Even the bad books told you something real about the Star Wars universe, something that all future books would have to account for and that other die hard Star Wars fans would regard as true.

Together, they formed a rich, coherent, fictional universe that transformed Star Wars from a set of great movies into one of the greatest galactic sandboxes of all time. That galactic sandbox was valuable precisely because every other Star Wars fan was also a part of it. Economists would call this a “network effect.” Or as Sunstein puts it, “People also tend to like things that other people like. . . . It might not even matter all that much if it is good!” (191-192)

After Disney purchased the intellectual property of Star Wars, the status of this universe was in doubt. When the newest movie was announced, Disney confirmed that the Expanded Universe would be replaced by the new movies. Acknowledging that “for over 35 years, the Expanded Universe has enriched the Star Wars experience for fans seeking to continue the adventure,” Disney was at pains to insist that the universe wasn’t really dead, because the old stories would live on as “legends.” But the Expanded Universe was dead in the sense that mattered. It no longer had the status of “canon,” – the official written record of the official Star Wars universe.

This was a disappointing fate, since the Expanded Universe had been carefully choreographed to be internally consistent and to steer clear of the periods to be developed in future movies. Indeed, fans rightly felt something of a betrayal, having bought and read (and sometimes endured) the Expanded Universe materials precisely because they were “canon.” How can you again love anything in the Star Wars universe if it might be retroactively repealed at any time?

It would be one thing to destroy this collectively-generated and widely-shared universe in order to make something great, like the original Star Wars trilogy. But for The Force Awakens!?

Yes, there is a democratic and populist impulse in eliminating the Expanded Universe. It was dense and obscure, and its elimination makes it a little easier for novices to warm to the franchise. As defenders of the repeal pointed out, superhero movies perpetrate this kind of “reboot” all the time.

But Star Wars was different. Or at least it was supposed to be. It made it possible, and rewarding, to be a true geek. It invited you to first love the movies and then discover how deeply things went. And because it was all “canon,” you were promised that the stories would fit together, and that other Star Wars geeks you had never met before would share the same interconnected network of stories. This kind of universe was important precisely because it’s so hard to develop. Alas, it is all too easy to destroy.

VI

This brings us back to Sunstein’s argument against “the myth of creative foresight” and in favor of serendipity. The many minds of the Expanded Universe partly support the argument – their shared world was richer than anything Lucas could have dreamed up on his own. At the same time, the Expanded Universe was great because it was centrally managed and promised to be canonical. An excess of improvisation laid the whole thing to waste.

Moreover, the destruction of the Expanded Universe (which is neglected in Sunstein’s book) makes the reader wonder if Sunstein’s enthusiasm is misplaced and inappropriate. Sunstein claims to have come to love Star Wars. But is it possible for him to truly love Star Wars without an appreciation of the Expanded Universe beyond the movies? How can anybody love Star Wars now, with the universe destroyed and the franchise pointed toward retreaded reboots?

VII

But maybe there is hope – hope that comes from a minor but ominous episode in 1997. In that year, George Lucas released a “special edition” of the original Star Wars trilogy, with several new scenes and alterations, mostly mediocre but mostly harmless.

There was one very harmful change, however, to one of the first scenes starring Harrison Ford’s Han Solo, who is threatened by a Rodian bounty hunter named Greedo. After a bit of tough talk, Han covertly shoots Greedo under the table, then tosses the bartender some money with the quip, “sorry about the mess.” The scene establishes Han’s character – the quick-shooting scoundrel.

But in the revision, Lucas had Greedo shoot first, and inexplicably miss despite shooting at point-blank range. This converts Han from crafty to lucky, and allows us to think that he’s the kind of a guy who would hesitate to launch a preemptive strike. The revision was so obviously wrong about the real Han Solo that it sparked the rallying cry, “Han Shot First!”—a reminder that there was a truth about the Star Wars universe even when the author tried to take it away from us.

That episode taught true Star Wars fans about the dark side of George Lucas. But it also taught us we could rally around a fictional universe, even when betrayed by its author. Fans could insist that the scoundrel version of Han Solo was really canon, even if the author himself disagreed.

So maybe the real lesson comes back to Sunstein’s “freedom of choice.” (193) Each of us can love our own version of the Star Wars universe. Sunstein is free to love the world of the movies that he recounts in his book. Others of us are free to love what we know to be the real Star Wars, unblemished by its creator – a galaxy far, far away, where the Extended Universe lives, space is still vast and trackless, and Han shot first.

Posted on 31 May 2016

WILLIAM BAUDE is Neubauer Family Assistant Professor of Law at The University of Chicago Law School.