By MICHAEL FALCONE

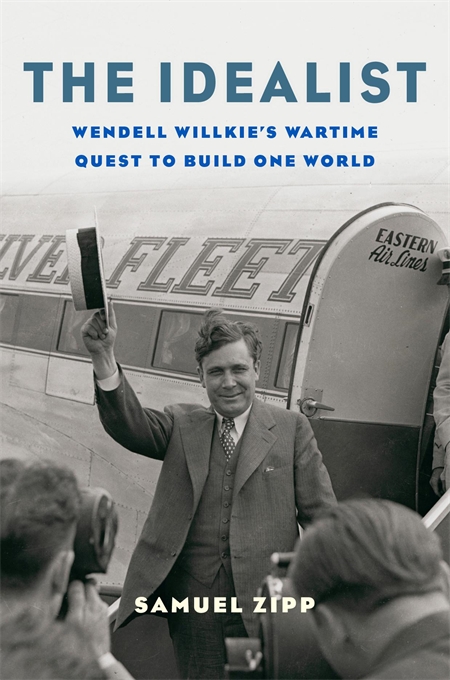

Review of The Idealist: Wendell Willkie’s Wartime Quest to Build One World, by Samuel Zipp

Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2020

At first blush, Wendell Lewis Willkie appears to be one of those Americans who was, to quote Graham Greene, “impregnably armored by his good intentions and his ignorance.” A rural Indiana lawyer turned corporate bigwig, anti-New Dealer turned antiracist radical, and failed presidential challenger turned loyal envoy to Franklin Roosevelt, Willkie seems to embody an impossible contradiction to contemporary audiences accustomed to hard political boundaries. Circling the globe in a rumpled blue suit, Willkie espoused idealistic notions about the cooperation of all the world’s peoples, and his optimism seems to belong to a different universe than the emergent cycles of cold war in our own times.

Yet for a few brief years in the 1940s, the brash and unrefined Willkie barnstormed onto the world stage and won the sympathies of millions with his hopeful ideas. His words filled the airwaves as he told the good news: An interdependent society of nations was possible, he said, and it could dispense once and for all with empire, exploitation, and war. Willkie called this vision “One World,” and he evangelized it through mass radio events, speeches, and a bestselling book. For all his popularity, however, Willkie also inspired legions of detractors, who believed his doctrine to be hopelessly naïve. At best, they said, it was an unsophisticated departure from the realities of global power politics, and at worst it represented a gullible underestimation of the wicked intentions of foreign peoples, from anticolonial independence leaders to shadowy Kremlin functionaries. From Walter Lippmann on the left to Clare Boothe Luce on the right, critics lined up to cast Willkie’s optimistic worldview as nothing more than “globaloney” (307).

Brown University historian Samuel Zipp has heard all these critiques before. To rectify what he perceives as their facile wrongs, he has written The Idealist, a new book on the fast life and poignant death of the romantic, populist internationalism that we might better call “Willkieism.” Zipp insists that easy accusations of gullibility and unsophistication underestimate the importance of Willkie’s crusade. “One World” matters, he tells us, because for an all-too-brief “Willkie moment” in the 1940s, millions of mainland Americans began seeing the world differently—and even believing that Willkie’s idealistic, empire-defying vision could be achievable (13).

It is a contention that asks us to revise our understandings of the United States’ growing global power in the 1940s, and particularly of the participation of a civil society that is often framed by historians as being merely along for the ride. By documenting the popularity of Willkie’s utopian ideas among a broad swath of the U.S. public, Zipp has given us an insightful, engaging, and thought-provoking study of a country in transition.

I

First things first: The Idealist is not a biography of Willkie. That has been done several times since his untimely death in 1944, with varying degrees of critical robustness. Nor is it an intellectual history of Willkie’s optimistic brand of small-world internationalism: the book does not dwell on the longue durée of internationalist thought, although it does give readers a primer. Instead we get something in between: The Idealist is the biography of an idea, a snapshot of the “precarious moment almost lost to our own cultural memory” that was Willkieism (14).

At the center is a chronicle of Willkie’s around-the-world goodwill trip in 1942, a formative experience that saw him fully awaken to a world rent asunder by war and anticolonial struggle. Chronological chapters document Willkie’s travels in North Africa, the Middle East, and Asia, but also function as guides to Americans’ changing attitudes toward the big things they would be forced to confront by a world shrinking in on them at midcentury: colonialism and empire, race, development, and the proper role of the United States in the world system. Zipp also squeezes in brief sketches of the geopolitical situation in regions, countries, and dependencies that many in the mainland U.S. had scarcely given thought to before 1942, much less formulated policy about.

The reader sees the world through the wide eyes of Willkie, the insular-but-curious American every-traveler, discovering the Other through the unprecedented contact enabled by the still-maturing technology of aviation. But while to Willkie the world seemed like a thrillingly romantic blank slate, the reader catches glimpses over his shoulder of the frighteningly quick and reflexive way the United States was already assuming dominion over others. When Willkie arrived in China, for example, he found U.S. military “advisors” impulsively forcing strategy on the chaotic Chiang Kai-Shek regime, even as the visitors fiercely disagreed on strategy themselves. A similar scene played out in Iran, as greenhorn U.S. troops arrived by the thousands to take over the country’s infrastructure from British occupiers.

Given scenes like this, it should come as no surprise that Willkie’s “cooperative internationalism” was probably never going to be workable in the context of an ascendant United States. The power of The Idealist, however, is in its emphatic recovery of the fact that Willkieism seemed sensible and even doable to many millions of people. Willkie’s America was buffeted by the self-contradictory impulses of anticolonialism and racism, yet its resolve to leave insularity behind and fashion a new order based upon ostensibly new ethics left ample room for “One World” to play out in the imaginations of newly-hegemonic Americans—if only for a few months.

II

The main set piece in The Idealist is Willkie’s 49-day, 28,000-mile, 12-country trip around the globe from August to October 1942. Not quite a private voyage (the trip was sanctioned and partially planned by the White House), yet not quite an official diplomatic mission either (Willkie travelled on his own initiative, labelled “Private Citizen Number One” by Franklin Roosevelt), the trip fell into a deliberate grey area. This ambiguity gave Willkie the space he craved to showboat and improvise as a back-slapping, glad-handing Hoosier, while giving Roosevelt plausible deniability for any diplomatic overreach his envoy might commit. This arrangement turned out to be prescient, as Willkie repeatedly gave speeches committing the United States to things—unsupervised self-determination for “the smaller nations;” a speedy second front in Europe—that proved awkward for a White House obsessively dedicated to holding its cards close to the chest.

Willkie’s primary job was to drum up support for the war among wavering allies and neutrals, but a more urgent mission dawned as the trip went on. Willkie already revered the anticolonial words—if not the pro-colonial deeds—of Woodrow Wilson, and was long predisposed to racial liberalism. But after weeks of impassioned discussions on the ground with anti-imperial nationalists, he also found himself jettisoning the shallow wisdom from Washington and London that calls for freedom among colonies and quasi-colonial mandates simply demonstrated insufficient ardor for the Allied cause. It was news to Willkie, and to most Americans, that many in the wartime “United Nations” alliance were not really interested in avenging Pearl Harbor, nor in relieving the plight of Europeans under Adolf Hitler. Indeed, sympathy for the Nazis was actively brewing in places like Egypt, Palestine, Iraq, and Iran, as desperate nationalists flailed for alternatives to British and French hegemony.

Newly aware that many of the world’s people were just as motivated to fight against Allied imperialism as Axis totalitarianism, Willkie pivoted away from milquetoast speechmaking toward a new quest and a new audience. He went home and made it his business to convince Americans that the true stakes of the war were to end Euro-American colonialism once and for all. Only then would the “peoples of the East” follow the U.S. into a post-imperial order based on goodwill and respect (13). That the U.S. should be the leader of such an order is little-problematized here, but that’s for a different book.

As the The Idealist thus argues, easy dismissals of Willkie as naïve downplay the fact that his true campaign was not about sentimentally creating a world government, but rather about educating the U.S. public that its own complicity in imperialism and racism blocked the path toward a peaceful world order. If the “One World” doctrine seemed utopian, it was partly because Willkie was in a hurry to show the possibilities of an alternative future. Willkie saw World War II as a historic but fleeting opportunity for true global change. Urgency pervaded everything he did and said. Thus, by the time his long, globe-circling journey was complete, he understood that, using Zipp’s pithy phrase, “in order to change how the world saw America, he would have to change how America saw the world” (140). But he would have to do it quickly, before the paralyzing complacency of peace set in.

Willkie would have his work cut out for him. Overseas, the ghost of Woodrow Wilson and the specter of Roosevelt’s liberty-trumpeting Atlantic Charter were leitmotifs everywhere Willkie went—which is to say that America’s self-interested prosecution of the war was constantly haunted by its leaders’ own toothless declarations of the freedom of all peoples. As anti-imperial nationalists from San Juan to Cairo to Xi’an well knew, lofty promises of self-determination had only ever cynically papered over the real dominion the United States then exercised over the world’s fifth-largest land empire, as well as the country’s ongoing collusion in maintaining the European imperial hierarchy. Meanwhile, back home, a minority of mainland Americans in 1944 had even heard of the Atlantic Charter, and many of the GIs in uniform barely knew what the country’s war aims were at all, beyond getting back to mom and baseball (274). As Willkie fretted, such was not the stuff of a U.S.-led worldwide anticolonial revolution.

Nevertheless, it is important not to broad-brush the entire domestic audience, and this is where Zipp’s study makes its most compelling historiographical contribution. There has been a boom in literature on U.S. internationalism and global thinking in recent years, but unlike The Idealist, many such works have focused on committees, think tanks, intellectuals, and high-level policymakers. The best of this scholarship makes a convincing case that the way U.S. hegemony shook out in the early Cold War period was—not to put too fine a point on it—a connivance of elites, whether it was the FDR administration cooking up the concept of “national security” (Emily Rosenberg, Andrew Preston); policy leaders laundering the reputation of U.S. imperialism through the U.N. (Stephen Wertheim); or internationalist intellectuals in Chicago drawing up plans for world governance in smoke-filled rooms (Or Rosenboim). Wendell Willkie, by contrast, was an “ugly American” in the original, positive sense—a hardworking farm boy made good. His internationalism was self-consciously a movement of the masses, his manifesto on sale at Woolworth’s for 25 cents.

Willkie was thus the anti-statesman. Although his antiracism would seem in historical memory to pit him against someone like America First’s fascist-in-chief Gerald L.K. Smith, his “populist internationalism” in fact made him more of a counterpoint to FDR himself. Roosevelt—that genteel, calculating wizard behind the curtain—was so unlike Willkie the populist idealist. Although FDR was no stranger to mass appeal, he was also saddled with competing commitments and constituencies, so much so that he was unable to climb down and fully join Willkie in playing on people’s raw sense of a shared global humanity. That is why sending his former campaign opponent around the world on his behalf made sense, and it is why the enthusiasm for a collaborative internationalism displayed by ordinary people so buoyed Willkie’s spirits. The importance of understanding Willkieism is thus to see that “One World” was a moment in which there was an appetite in the United States for knowledge about the rest of the world, and room for cooperative idealism in foreign policy in the minds of millions of ordinary Americans. We join Zipp in sighing at the could-have-been represented by this scarcely-recognizable chimera.

At the same time, The Idealist perhaps gives Willkie too much credit for the ideas behind Willkieism. The narrative discusses but does not dwell on the fact that among the most profound influences on Willkie’s worldview were women and people of color, especially the journalist Irita Van Doren and the NAACP leader Walter White. Moreover, Willkie’s framing of racism and segregation as forms of internal colonization drew from and was at home alongside existing, longstanding civil rights and anticolonial critiques, from W.E.B. Du Bois to the “Double V” campaign. Willkie’s written manifesto, the book One World, simply joined the fray as an ephemeral statement of alliance—one more point on the long arc between Martin Delany and Malcolm X.

But Willkie’s popularity nevertheless served as a conduit to the mainstream for the anticolonial ideas of nationalists abroad and civil rights campaigners at home, and did so in a populist way aimed at a wide spectrum of the lay public. It is largely forgotten now, but One World was one of the bestselling books of the twentieth century. Willkie’s broad constituency ranged from coastal liberal whites to the educated middle classes to segments of the Black intelligentsia, and his post-voyage “Report to the Nation” was heard by 36 million radio listeners. Considering Willkieism’s explosively progressive content, those are serious numbers, and historians should take them more seriously as testimony to a nascent multiracial, pan-partisan internationalist movement, however fragmented or short-lived it might have been. The story Zipp gives us thus avoids the trap of being just another old-school white-man history.

Of course, from the evidence given—newspaper and diplomatic reports, memoirs, extensive historiographical mining, and Willkie’s own words (the latter often attenuated by Zipp’s interpretive filter)—some readers might reach dissenting conclusions from the author about Willkie and his times. Some might judge him as a mere opportunist, or else a boor who stumbled into a movement that was not his own. It would be reductive, however, to look at the shallowness of Willkie’s plans, his blindnesses to U.S. empire, and the baked-in self-righteousness of his vision for U.S. foreign relations, in order merely to dismiss “One World” out of hand.

Instead, what we find peeking between the lines of The Idealist is a striking milestone, one that ought to merit more attention from historians (and more forceful insistence from Zipp): However much Willkie was a bull in a China shop and a diplomatic neophyte, his articulation of goals for the coming world order—particularly through major speeches in Tehran and Chongqing as FDR’s quasi-envoy—represented the first time in the history of anything approaching official policy that the United States committed to antiracism as a basis for its foreign relations. For that reason alone, Zipp’s guided tour through Willkie’s brief turn in the limelight matters.

The book’s real work is thus to explore the possibilities of a contingent historical moment, one in which “One World” seemed to millions of people like it might just be possible. Set as it was in a white supremacist and hitherto-neutral republic, it must have seemed like a provocative manifesto indeed. The awkward corner of dissimulation in which Willkie’s movement put Roosevelt (and the less-awkward corner of imperial bombast in which it put Winston Churchill) tells us volumes about the double-dealing that the principal Allies engaged in while planning for the postwar order. It also does much to reveal the gulf between the rhetoric of the Atlantic Charter and the real intentions of the war’s major players. Framing Willkieism as merely shallow or saccharine or paternalist (and it was all of those things) misses the point.

III

All in all, The Idealist is a perfect book for graduate seminars or history discussion groups. It offers a useful, contextualizing primer on the state of a world over which the United States was about assert hegemony, with each narrated stop on Willkie’s tour jam-packed with capsule histories and summaries of many of the finest scholarly works of the last decade. The book also provides a useful “state of the subfield” of academic U.S. foreign relations history. Every contextual paragraph conceals an iceberg of historiography (and, indeed, sometimes Zipp seems at pains to squeeze in mention of every caveat and revision currently under contention among diplomatic historians on this or that subject). The book does an admirable job of spacing out all this context to fit into a natural-seeming narrative that is relevant to the Willkie story. Most importantly, The Idealist deals in big-picture issues that stoke myriad questions in readers’ minds, while leaving several thorny ones unresolved. It is worth briefly considering a few of them now.

For one thing, an obvious hole in Willkie’s “One World” vision was its inability to address what happens if the cooperative, interdependent global order failed to prevent bellicosity or domination. In 1944, Willkie’s old friend Walter Lippmann, keeping a Northeastern Atlanticist’s eye on the recent history of Europe, identified the yawning bear-trap facing Willkieism: Its “assumption that everything is everybody’s business” might logically lead to a “license to universal intervention” for future world powers (279). Willkie would unlikely have endorsed such an interpretation, of course. But his inability to explain the actual cohesive forces of collaborative internationalism amid a broken world—as well as his acceptance of autocracy and corruption as sometimes-permissible stepping stones on the path to democratic self-rule—made his doctrine hauntingly compatible with that of Harry Truman four years later. The so-called Truman Doctrine similarly threw in its lot to “support free peoples” without delineating any practical criteria for engagement or enforcement.

Willkie assumed that world unity would come from a mix of shared liberal ideas and technological change, gifts of modernity that would inevitably bring the disparate peoples of the earth closer together. But he was hardly the only shrinking-world determinist. In fact, drawing from intellectual traditions like the continental hegemony theories of Halford Mackinder, influential policy elites—ranging from the scholars at Princeton’s Institute for Advanced Study to Franklin Roosevelt himself—spent the 1930s constructing a technological-geographic determinism not dissimilar to Willkie’s. The difference was that they drew a much bleaker lesson from the ongoing annihilation of time and space wrought by modern technology: To them, global interdependence was not a friendship opportunity but a security threat, and it demanded new military buildup, as well as a more muscular interventionism to ensure the protection of U.S. interests everywhere on earth. Thanks to the very intimacy that Willkie so welcomed, the whole globe would now be an American “sphere of influence.”

IV

The fact that the same phenomenon could lead to such radically divergent conclusions leads us to ask if the true importance of Willkie lay not in the historical memory of his brief moment in the spotlight, as Zipp suggests, but rather in what Willkie’s failures tell us about the ways policymakers use, appropriate, and exploit history and historical understanding when formulating grand strategy.

To be more specific: Zipp stakes Willkie’s significance in part on the long afterlife of the “One World” idea, which he sketches briefly in the conclusion, from Jawaharlal Nehru and Léopold Senghor to Silicon Valley utopian libertarianism and Thomas Friedman-esque flat-world globalism. But just as important as looking forward from 1944 is looking backward to the 1930s, to see how quickly the memory of the Depression decade fractured in the 1940s into a new set of foreign relations truisms.

By 1943, the increasingly discordant factions of internationalist thinkers could agree on only one thing: That the 1930s, Hitler, and outbreak of war had proven them right. To prevent the world from endlessly stepping on the same lethal rake, any reasonable person could now surely see, as they did, that an organized international system with universal buy-in was necessary and inescapable.

Beyond that, however, “internationalist” schools of historical and strategic thought were quickly pulling apart. By the end of World War II, the mainstream internationalist elite—from Henry Luce to Lippmann to Hans Morgenthau—had coalesced around the idea that the real lesson of the 1930s was that the fight against totalitarianism (and its more threatening offspring from the American perspective: disorder) was an issue for peacetime. Concessions and conciliatory diplomacy with fascist regimes in the 1930s had only led to vulnerability and war. Now, budding “nationalist globalists” (a term used by John Fousek, Jenifer Van Vleck, and others) turned their gaze from the soon-to-be vanquished Germany to the USSR. They looked at Soviet designs on Poland with grave suspicion. Already uneasy with the wartime alliance with Moscow, they saw the USSR’s postwar maneuvering in Eastern Europe as confirmation of their devastating logic: the last totalitarian power standing was following the lead of its fascist predecessors in waging clandestine bellicosity during peace—a clear violation of the rules-based order, and almost a demand for an aggressive response.

But Willkie defied this “Munich logic.” Although he did not live to see the end of the war, he openly rejected the events of the 1930s as a universally applicable geopolitical lesson. He forcefully exhorted the nation not to apply them to Stalin and the USSR, whom he saw as motivated by pragmatism and caution, not zealotry (171). In his view, the realities of industrial development and a shared commitment to practical mutual advantage—paired with careful diplomatic soothing of Stalin’s suspicious ego—would almost certainly achieve an effective level of sustained cooperation between Moscow and Washington. But by viewing the United States and Soviet Union as, to use Zipp’s memorable phrase, “two great ships headed into harbor on a returning tide,” Willkie stepped out of the gathering mainstream of internationalist thought on the world balance of power (143). It was a stand that would bring him widespread scorn in his last days.

Willkie was thus a vocal, vanguard figure for internationalism when the country had been divided between internationalism and so-called isolationism. But changing ideological tides—which he partially helped to bring about by energetically campaigning for the United States to think globally—soon swamped him. By the end of his life he had become one more globalist voice amid a dissonant chorus of them, most of whom were to his right and appealing to far baser instincts. “One World” gave way to precisely the “narrow nationalism” that Willkie had always opposed.

It is worth remembering that that other most quoted interpreter of Soviet motivations, the State Department soothsayer George Kennan, shared Willkie’s view that Moscow was motivated by pragmatism. The USSR, Kennan argued in his “Long Telegram” in 1946, was cowed by shows of strength, infatuated with pride and prestige, and in no real hurry to dominate the world. Like Willkie, Kennan argued that the strategic solution to the rise of the Soviet Union would be for the United States to live up to its own democratic rhetoric, committing to a positive and constructive role in the world beyond mere abstractions about “freedom.”

The difference between Kennan and Willkie was that Kennan saw Stalin and his party acolytes as irredeemably dishonest brokers. They were innate manipulators, he insisted, whose illegitimate brand of power rested on secrecy and duplicitousness—a temperament fundamentally incompatible with Willkie’s idealistic world system of mutual trust. Both visions called for national introspection, commitment, and hard work, but that of Kennan had the benefit of appealing to nationalist globalists, conservative raw-power realists, and rules-fixated liberal internationalists alike. Kennan thus provided a pretext for aggressive containment in a way that Willkie’s short-lived and optimistic movement had no answers for. If Willkie’s ideas appealed to Americans’ better angels, those of Kennan appealed to the more intractable worldviews of the people who ultimately called the shots.

Keeping the above dichotomy in mind as we read Zipp’s book leads us to ponder one final, related issue: The power of mass public opinion in American life—or lack thereof. One of the book’s central contentions is that not only was Willkie’s stance against “narrow nationalism” and his commitment to “militant idealism” unprecedented at such a scale in the U.S. experience, but also that it had an effect—that millions of mainland Americans thought anew about the United States and its place in the world, drawing inspiration from Willkie’s humanizing portraits of peoples enacting “their version of the American Revolution” around the globe (7).

Even if one might quibble with the reliability of Gallup polling in the 1940s or the anecdotal nature of public letters written to Willkie’s office, the fact remains that the millions of books sold, the agitation Willkie caused among prominent public figures, and even the (fleeting) interest of Hollywood, all seemed to suggest that “One World” was indeed something seismic. Yet so little came of it all, a disjuncture noted by historical actors at the time. Zipp observes that for all of Willkie’s public purchase, elite policymakers and functionaries in the State Department remained utterly unmoved by his diplomatic platform, continuing to draft blueprints “behind closed doors” for the world order ahead (250).

This leads us to ask, at the risk of being overly simplistic, whether a mass movement can really guide the direction of hard-headed power politics in modern U.S. diplomacy. More specifically, we might ponder whether what the Willkie moment truly captured was the end of the diffuse, decentered, federalist U.S. political system—riven and torn into its many vested and localized interests—and the dawning, in its place, of what analysts since the 1960s have called the “imperial presidency.”

The executive has long sought to bend public opinion toward its desired foreign policy goals, usually opportunistically, often cynically. But as academic historians like Emily Rosenberg, Fredrik Logevall and Campbell Craig, and Andrew Preston have demonstrated, at the beginning of the Atomic Age things became markedly different. Even as the cooperation-minded book One World flew off the shelves nationwide, in the corridors of power it was the hard-headed pursuit of “national security” that came to define U.S. foreign policy, full stop. In the years ahead, Congress would abdicate its position as a coequal arbiter of strategy—often willingly—and usher in an antidemocratic paradigm of top-down command that sapped deliberation and inclusivity in U.S. foreign relations.

Willkie’s bet that he could shape U.S. diplomatic commitments by winning the hearts and imaginations of a broad, reasonable middle seemed to make perfect sense at the time, given that much of his career—from testifying against the New Deal to campaigning for the Lend-Lease Act—had centered on public and congressional opinion. Yet it was precisely that focus on public power and the attempt to alter the “political and social imaginations of all the world’s peoples, even ordinary Americans,” that makes the Willkie moment seem like a coda (7). Willkie’s populist idealism, and his intended grand domestic coalition for “One World” thinking, was already in the process of being subverted, no matter which brand of internationalism his movement came to support.

This is a much darker lesson than the one Zipp gives us. The book ends with a leap through the intervening decades, culminating with a call to remember the truths and possibilities behind Willkie's idealism in today’s moment of fracture. But in the United States at least, Willkie’s vision was interred not long after he was, defeated on one side by isolationism’s transformation into raw nationalism—using some of the same abstractions of “freedom” that Willkie so championed with “One World”—and on the other by the last vestiges of cooperative internationalism lapsing into hegemonic globalism.

As Zipp concedes, Willkie’s ideas lived on not with Americans attempting to understand the world, but rather with anticolonialists, nonalignment theorists, and independence leaders attempting to understand the ugly contradictions of U.S. hegemony. If “One World” guided American public opinion for a time, public opinion seems to have done little to guide America’s world after Willkie’s hopeful voice fell silent.

Posted on 21 October 2020

MICHAEL FALCONE is a postdoctoral fellow at the Brady-Johnson Program in Grand Strategy at Yale University. He specializes in diplomatic history and the history of technology.