By NICHOLAS BUCCOLA

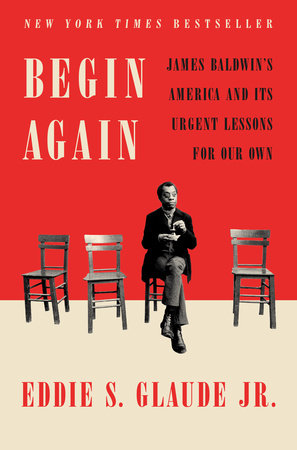

Review of Begin Again: James Baldwin's America and Its Urgent Lessons for Our Own, by Eddie S. Glaude, Jr.

New York: Crown, 2020

Eddie S. Glaude’s Begin Again is right on time. The perils of white supremacy are always urgent for folks at the margins of our society, but this book arrives in a historical moment when it appears the broader zeitgeist is more attentive to these perils than usual. Thus Glaude, the James S. McDonnell Distinguished University Professor at Princeton, has achieved a rare feat: he has written an intellectually serious and challenging book that has gained the attention of many readers beyond the academy, with the book even climbing onto the New York Times bestseller list.

The subject of Begin Again is captured in its subtitle: “James Baldwin’s America and Its Urgent Lessons for Our Own.” In the introduction, Glaude calls the book “strange” due to its defiance of genre. It is sometimes autobiographical, sometimes historical, sometimes philosophical, and sometimes polemical. And it is sometimes all of these things at once (xviii). This “strangeness” is one of book’s great virtues and other writers would do well to follow Glaude’s lead in breaking free of the strictures of genre. Begin Again is just what it needs to be in order to do what it needs to do. This is what writing ought to be.

Begin Again is an invitation to think with Glaude as he thinks with Baldwin. And so, readers will find themselves witnessing an all-night discussion half a century ago between Baldwin and student revolutionaries on one page and examining the latest atrocities of Donald Trump on the next. This moving back and forward and back again can be demanding for the reader, but it is necessary for Glaude to do what he needs to do in the book. “History,” Baldwin teaches, “is present in all that we do.” By traveling back with Baldwin, we can better understand why he did what he did and how we got where we are; and when Glaude brings Baldwin’s lens to bear on the world around us, we can better see what is happening in our moment.

Glaude’s journey back in time to sift through the “wreckage and rubble” of Baldwin’s life and writings has a very specific point of departure. Glaude originally set out to write an intellectual biography of Baldwin but moved away from that project as he was pulled toward the sort of book the times demanded. Glaude sat down to write Begin Again in the shadow of “the country’s latest betrayal: The promise of the election of the first black president had been met with white fear and rage and with the election of Donald Trump” (xxiv). In the wake of this betrayal, Glaude turned to Baldwin in a quest to find answers to some urgent questions. “What do you do when you have lost faith in the place you call home?” (xvii) What do you do when hope fades and “you are left with the belief that white people will never change—that the country, no matter what we do, will remain basically the same?” (xvii) How did Baldwin, Glaude asks, “[navigate] his disappointments” and how did he maintain “his faith that all of us, even those who saw themselves as white, could still be better?” (xxiii-xxiv)

In order to answer these questions, Glaude travels back to a Baldwin who may be less familiar to many readers. There is a dominant narrative about Baldwin that posits he was in his “prime” between 1953 (the year Go Tell It On the Mountain, his first novel, was published) and 1963 (the year The Fire Next Time, his most famous nonfiction book, was published), and that his later work is marked by declining quality and waning influence. Glaude rejects this dominant narrative and one of the seminal scholarly contributions of this book is his defense of Baldwin’s later works, especially No Name In the Street (1972). These later works matter, Glaude argues, because they allow us to make sense of the less hopeful Baldwin, the Baldwin who had the deaths of Medgar Evers, Malcolm X, Martin Luther King, Jr., and so many thousands more weighing down on his mind, heart, and soul. How did this Baldwin manage to survive, let alone maintain any semblance of hope for a country not quite soulless, but certainly not soulful?

One of Glaude’s answers to this question is that Baldwin was not carried away by despair because he remained anchored by certain philosophical commitments. On Glaude’s reading, interpreters who find a different Baldwin in the later works are, in a fundamental sense, wrong. Baldwin remained remarkably consistent, but the times changed and, as a result, the implications of his position—both in terms of diagnosis and prescription—became all the more radical. This radicalism made some of Baldwin’s contemporaries and later interpreters uncomfortable, but that says more about them, Glaude argues, than about the author himself.

So what were those core philosophical commitments that Baldwin clung to as he watched the freedom dreams of the 1960s fade? The first insight is what Glaude calls “the lie,” which is “more properly several sets of lies” that make up the intellectual architecture of white supremacy. Among these lies, two stand out as especially important: the “value gap” and willful American innocence. The term “value gap” comes from Glaude’s last book, Democracy in Black, and it is meant to capture the ways in which our attitudes, practices, and institutions place greater value on white lives. Something like this idea was at the core of Baldwin’s philosophy. “What do Negroes want?” Baldwin was asked again and again. “We want to be treated like human beings,” he would say in response or, when he was in his Socratic mode, he would respond with a question: “what do you want? There is your answer.”

In order to maintain this fundamental lie, Glaude explains, Americans have willfully ignored and distorted their history in order to preserve a sense of innocence. As Baldwin wrote in 1962, “it is the innocence which constitutes the crime.” The trouble with the American soul is that we know—on some level—what we have done. Whatever our virtues and triumphs as a country, they exist alongside the fact that genocide and slavery are cornerstones of the republic. Our “fatal flaw,” as Baldwin put it, is that we recognize a human being when we see one (9). However much we rationalize and mythologize and patronize in our quest to purify our history, we are haunted by the fact of the humanity of those who have been trampled by the march of American “progress.” But this is a truth that most Americans would rather not discuss and so, when we are reminded of it, we tend to get rather defensive. Have you noticed in your personal life how you tend to lash back hardest against criticisms that strike you—in your most private, honest moments of introspection—as true? Apply that idea to the country and you have a sense of Baldwin’s—and Glaude’s—diagnosis of what ails the American soul.

With “the lie” as the foundation of his analysis, Glaude devotes the core of Begin Again to thinking with Baldwin about history, morality, identity, and politics. The reader is taken at a steady clip from the integration crises of the 1950s to Baldwin’s last encounters with Martin Luther King, Jr. in the late 1960s to the white supremacist “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville in 2017, back again to the 1960s to witness the rise of Ronald Reagan, and so on. This moving back and forward and back again proves to be revelatory. When Glaude travels back in his chapter on “the symbols and uses of American history” (“The Dangerous Road”), he plays the role of historical interpreter with precision and force and when he brings us into the present, there is Baldwin by his side, helping writer and reader see what might otherwise be obscured. Because Glaude moves backwards and forwards so deftly, readers see important episodes in Baldwin’s life and writing in a new light. With the haze of the torches of Charlottesville still lingering in the air, for example, we confront Baldwin in 1965, proclaiming:

White man, hear me! History, as nearly no one seems to know, is not merely something to be read. And it does not refer merely, or even principally, to the past. On the contrary, the great force of history comes from the fact that we carry it within us…(“The White Man’s Guilt”)

When these words hit newsstands in August 1965, Watts was burning. As we revisit Baldwin’s words with Glaude, Heather Heyer is dying in the street in Charlottesville, struck down by a white supremacist terrorist. Backwards, forwards, and back again. Herein lies the magic of Begin Again.

Lest it seem that Glaude is only concerned with relatively abstract concepts like “historical memory” and “symbolic politics,” it is worth noting his forays into political questions that may strike some readers as a bit “closer to the ground.” In a chapter called “The Reckoning,” for example, Glaude adroitly navigates two minefields of controversy: Baldwin’s sometimes strained relationship with Black Power activists and “the illusions of an easy identity politics” in our present moment (113). In a Baldwinian fashion, Glaude weaves these two lines of reflection together and in so doing, makes insights that might otherwise be missed.

Glaude begins his thoughts on Baldwin and Black Power with the inauguration of Ronald Reagan as Governor of California in January 1967. This is just the right way to start such an analysis. Baldwin was always obsessed with the ground out of which political phenomena grew. Ronald Reagan is far less interesting than what his rise reveals about the moral and political culture that created him. The ideologies and activities of various Black Power groups are less important than what their rise can teach us about the atmosphere in which they thrived. Getting a better sense of how Baldwin did this sort of analysis in his own time can help us better understand our own political moment.

Baldwin’s view of Black Power, Glaude points out, was marked by “nuance and complexity.” He was sympathetic to—and felt—the rage of Black Power activists, found some things to admire in the philosophy (e.g., his eventual embrace, with Black Panther Bobby Seale, of “a Yankee-Doodle type socialism”), and he was often willing to defend them against dismissive or ignorant critics. At the same time, Baldwin confronted harsh criticisms from some Black Power activists (most notoriously Eldridge Cleaver) who dismissed the writer as insufficiently radical, among other things. But Baldwin’s criticisms of Black Power were not rooted in mere defensiveness. Glaude points out that Baldwin worried about “the turn to separatism,” “solidarity based on some essential, fixed idea of blackness,” and an over-reliance on an enemy to define oneself. “I would like us to do something unprecedented,” Baldwin wrote in 1967, “to create ourselves without finding it necessary to create an enemy” (as quoted in Begin Again, 91).

Baldwin’s nuanced position, which was simultaneously sympathetic and critical, placed him in what Glaude calls a “no-man’s-land” in a “Manichean world.” Glaude describes the toll exacted on Baldwin as he was attacked from “both sides” during the last two decades of his life. With this history in mind, Glaude’s next move in the book—to offer his own nuanced and complex position on contemporary “identity politics”—is bold and courageous. This is another moment when Glaude’s decision to incorporate autobiographical reflections proves to be an inspired choice and I believe it is a choice Baldwin would have admired. Glaude, like Baldwin, runs the risk of finding himself in a “no-man’s-land” in a “Manichean world.” He is among our most prominent public intellectuals—a university professor at an elite institution, a columnist for Time magazine, a contributor to a major news network, a bestselling author, and so on—and he is also an activist whose core commitment is to doing the work necessary to achieve racial justice. Glaude is in the rare position of having both an elite audience and the ear of many activists who are in midst of changing the face of the country. Glaude is a serious and principled thinker and his primary obligation is to the truth, even when the truth might lead to pushback from one or both of these audiences. But like Baldwin, Glaude is here as a “kind of Jeremiah” and so his duty is to say things folks might not want to hear.

When Glaude does this potentially treacherous work of thinking through Baldwin’s urgent lessons for our political moment, his conclusions are striking. Glaude calls on all of us—right and left—to abandon “easy identity politics.” The American Right, which is fond of criticizing “identity politics” at every turn, is dominated by the basest identity politics imaginable. They take “their whiteness, their straightness, their maleness for granted” (or their aspirations to whiteness, straightness, or maleness) and time and again they double down on their exclusionary identities in order to enhance their power (or feeling of power) in the world. If you want to learn what “easy identity politics” looks like, just subject yourself to five minutes of the rantings of Tucker Carlson. And Glaude reminds us of something we must never forget: Trump and his enablers are not dramatic departures from the norms of American political life. These merchants of hate and perpetuators of the lie have been here all along and they are likely to remain on the scene long after Trump and his band of grifters have faded from memory.

So what is to be done with those who cling to the lie? Glaude argues that we simply cannot spend our precious energy attempting to save folks who remain entranced by the delusion of white supremacy. Here again, Baldwin has something to teach us. By the late 1960s—after he had witnessed all of the assassinations and watched the rise of the “law and order” politics exemplified by Nixon and Reagan—Baldwin refused to devote the time he had left to trying to save those “who saw themselves as white” (xxiii). These folks might yet achieve salvation, but he refused to shoulder the burden of that salvation. In this period, we see what the writer Michael Thelwell calls “the shift in Baldwin’s we” (xxiii). The lie is irredeemable. Baldwin was reticent to reach the same conclusion about those caught in the trap of the lie, but he was tired expending energy to help them achieve a salvation they resisted so fervently.

But what is the remaining we supposed to do? Glaude says folks on the American Left must avoid other sorts of traps. We must avoid reductionist class politics that discount the importance of race matters in our history. We must also reject the “facile identity politics (with no serious policy content)” all too often offered by elites. And Glaude also calls on folks at the grassroots to resist “the illusions of an easy identity politics” that offer “comfort and safety in the appeal to unique experiences that are essentially our own and bind us to others like us” (113). On this point, he calls on us to follow Baldwin’s demand we “grow up” out of our “swaddling clothes” by avoiding categories that “shut us off from the complexity of the world and the complexity within ourselves” (115).

In the place of these traps, Glaude calls on us to “work, with every ounce of passion and every drop of love we have,” to bring about a “revolution of value” that will lead to the implementation of policies that might “remedy generations of inequities based on the lie” (114-115). As we do this work, we must find solidarity where we can and create new identities that do not rely on the creation of an enemy. The energy generated at the grassroots is vital to this revolution. Elites will always lead from behind. It is up to the people themselves to exercise the radical imagination necessary to bring about meaningful change.

While Glaude’s prescription for grassroots politics exudes an unabashed idealism, his prescription for elite politics is marked by a strong dose of realism. His adoption of this position, he confesses, is a departure from where he stood just four years ago. In the midst of the 2016 campaign, Glaude could not bring himself to vote for Hillary Clinton and, prior to the Republican nomination of Donald Trump, he urged black voters to leave the presidential ballot blank. With the nomination of Trump, Glaude modified his position and encouraged black voters in battleground states to vote for Clinton while encouraging others (in safely red or safely blue states) to pursue the “blank out” strategy in order to send a message of dissatisfaction to the Democratic Party.

Four years on, Glaude has the courage to do something public figures all-too-rarely do: he says he was wrong. His 2016 position was based on the belief that “white America would never elect such a person to the highest office in the land. I was wrong, and given my lifelong reading of Baldwin, it was an egregious mistake.” I appreciate Glaude’s willingness to acknowledge the flaws in his political prognostication, but the wrongness that really matters here is that which was exhibited by the millions of voters whose journey to the polls was fueled by the delusion of the lie. And millions of American voters have proven, time and again, that the lie is a habit they just cannot kick. At the level of elite politics, then, we must stop pretending that these addicts can be saved. Instead, we must push elite politicians to stop just “playing it safe” and we must pressure elites to address structural inequality. But we must also sometimes recognize that we have to “buy more time” and set up safeguards that might protect innocent people from the wrath of those animated by the delusion of white supremacy.

The spirit of Begin Again is marked by “a hope, not hopeless, but unhopeful.” These are the words of the great W.E.B. DuBois, and they are an apt description of Baldwin’s position by the end of his life. They fit Glaude as well. Glaude has come to terms with the fact that there are many Americans—those who cling to whiteness as the core of their identity and those who aspire to become “junior partners,” to borrow a term from Frank Wilderson III, in the project of white supremacy—who hold views that are fundamentally irredeemable. Their power and their intransigence make it impossible to be hopeful about the future of this country. And yet, to give up hope altogether is to concede final victory to the perpetuators of the lie. This will not do. In the moments of our greatest despair, we would do well to remember the words of Baldwin that inspired Glaude’s title: “Not everything is lost. Responsibility cannot be lost, it can only be abdicated. If one refuses abdication, one begins again.”

Posted on 17 September 2020

NICHOLAS BUCCOLA is the author of The Fire Is upon Us: James Baldwin, William F. Buckley Jr., and the Debate over Race in America (Princeton University Press, 2019) and his work has been featured in The New York Times, Salon, and Dissent. He is the Elizabeth and Morris Glicksman Chair in Political Science at Linfield University in McMinnville, Oregon.